Persepolis

Persepolis was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BC). It is situated in the plains of Marvdasht, encircled by southern Zagros mountains of the Iranian plateau. Modern day Shiraz is situated 60 km (37 mi) southwest of the ruins of Persepolis. The earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. It exemplifies the Achaemenid style of architecture. UNESCO declared the ruins of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979.

The complex is raised high on a walled platform, with five "palaces" or halls of varying size, and grand entrances. The function of Persepolis remains unclear. It was not one of the largest cities in Persia, let alone the rest of the empire, but appears to have been a grand ceremonial complex that was only occupied seasonally; it is still not entirely clear where the king's private quarters actually were. Until recently, most archaeologists held that it was primarily used for celebrating Nowruz, the Persian New Year, held at the spring equinox, which is still an important annual festivity in modern Iran. The Iranian nobility and the tributary parts of the empire came to present gifts to the king, as represented in the stairway reliefs.

It is also unclear what permanent structures there were outside the palace complex; it may be better to think of Persepolis as only one complex rather than a "city" in the usual sense. The complex was taken by the army of Alexander the Great in 330 BC, and soon after its wooden parts were completely destroyed by fire, likely deliberately.

Geography

Persepolis is near the small river Pulvar, which flows into the Kur River.

The site includes a 125,000 m2 (1,350,000 sq ft) terrace, partly artificially constructed and partly cut out of a mountain, with its east side leaning on Rahmat Mountain. The other three sides are formed by retaining walls, which vary in height with the slope of the ground. Rising from 5–13 m (16–43 ft) on the west side was a double stair. From there, it gently slopes to the top. To create the level terrace, depressions were filled with soil and heavy rocks, which were joined together with metal clips.

History

Reconstruction of Persepolis, capital of the Persians

Darius the Great, by Eugène Flandin (1840)

Construction

Archaeological evidence shows that the earliest remains of Persepolis date back to 515 BC. André Godard, the French archaeologist who excavated Persepolis in the early 1930s, believed that it was Cyrus the Great who chose the site of Persepolis, but that it was Darius I who built the terrace and the palaces. Inscriptions on these buildings support the belief that they were constructed by Darius.

With Darius I, the sceptre passed to a new branch of the royal house. Persepolis probably became the capital of Persia proper during his reign. However, the city's location in a remote and mountainous region made it an inconvenient residence for the rulers of the empire. The country's true capitals were Susa, Babylon and Ecbatana. This may be why the Greeks were not acquainted with the city until Alexander the Great took and plundered it.

General view of the ruins of Persepolis

Aerial architectural plan of Persepolis

Persepolis in 1920s, photo by Harold Weston

Darius I's construction of Persepolis was carried out parallel to that of the Palace of Susa. According to Gene R. Garthwaite, the Susa Palace served as Darius' model for Persepolis. Darius I ordered the construction of the Apadana and the Council Hall (Tripylon or the "Triple Gate"), as well as the main imperial Treasury and its surroundings. These were completed during the reign of his son, Xerxes I. Further construction of the buildings on the terrace continued until the downfall of the Achaemenid Empire. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, the Greek historian Ctesias mentioned that Darius I's grave was in a cliff face that could be reached with an apparatus of ropes.

Around 519 BC, construction of a broad stairway was begun. The stairway was initially planned to be the main entrance to the terrace 20 m (66 ft) above the ground. The dual stairway, known as the Persepolitan Stairway, was built symmetrically on the western side of the Great Wall. The 111 steps measured 6.9 m (23 ft) wide, with treads of 31 cm (12 in) and rises of 10 cm (3.9 in). Originally, the steps were believed to have been constructed to allow for nobles and royalty to ascend by horseback. New theories, however, suggest that the shallow risers allowed visiting dignitaries to maintain a regal appearance while ascending. The top of the stairways led to a small yard in the north-eastern side of the terrace, opposite the Gate of All Nations.

Grey limestone was the main building material used at Persepolis. After natural rock had been leveled and the depressions filled in, the terrace was prepared. Major tunnels for sewage were dug underground through the rock. A large elevated water storage tank was carved at the eastern foot of the mountain. Professor Olmstead suggested the cistern was constructed at the same time that construction of the towers began.

The uneven plan of the terrace, including the foundation, acted like a castle, whose angled walls enabled its defenders to target any section of the external front. Diodorus Siculus writes that Persepolis had three walls with ramparts, which all had towers to provide a protected space for the defense personnel. The first wall was 7 m (23 ft) tall, the second, 14 m (46 ft) and the third wall, which covered all four sides, was 27 m (89 ft) in height, though no presence of the wall exists in modern times.

Architecture

Persepolitan architecture is noted for its use of the Persian column, which was probably based on earlier wooden columns. Architects resorted to stone only when the largest cedars of Lebanon or teak trees of India did not fulfill the required sizes. Column bases and capitals were made of stone, even on wooden shafts, but the existence of wooden capitals is probable. In 518 BC, a large number of the most experienced engineers, architects, and artists from the four corners of the universe were summoned to engage and with participation, build the first building to be a symbol of universal unity and peace and equality for thousands of years.

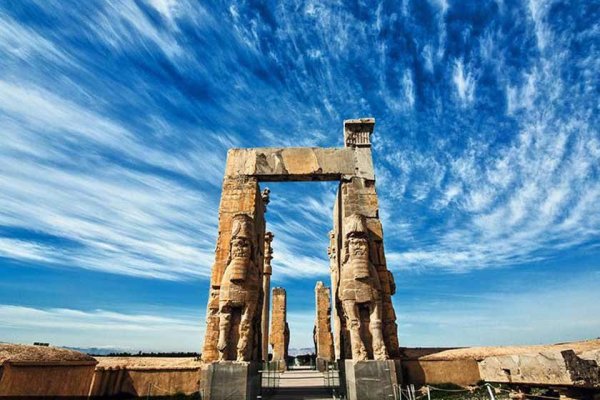

The buildings at Persepolis include three general groupings: military quarters, the treasury, and the reception halls and occasional houses for the King. Noted structures include the Great Stairway, the Gate of All Nations, the Apadana, the Hall of a Hundred Columns, the Tripylon Hall and the Tachara, the Hadish Palace, the Palace of Artaxerxes III, the Imperial Treasury, the Royal Stables, and the Chariot House.